June 6, 2023

As a DevOps Enginerd, I’m keen to work with developers, helping them onboard their applications to CI/CD pipelines. If you’re wondering, a CI/CD pipeline is essentially multiple automations linked together; a git commit -m "I changed all the things" command results in a change to a live application (following the good ole’ DEV/TEST/PRE-PROD/PROD pathway, of course!). Unfortunately, there is often a gap between being able to run an application on a laptop and onboarding it to an enterprise-grade CI/CD pipeline, mainly because so many things can go wrong. Admittedly, containerizing an application isn’t particularly new in 2023, but adding the combined power of Cockpit and Podman to a development toolchain adds some nifty functionality – helping to bridge the gap by adding the ability to graphically manage (and even create) containers on individual servers, proving an app works without entering the morass that can be on-boarding to a CI/CD pipeline.

What is Cockpit?

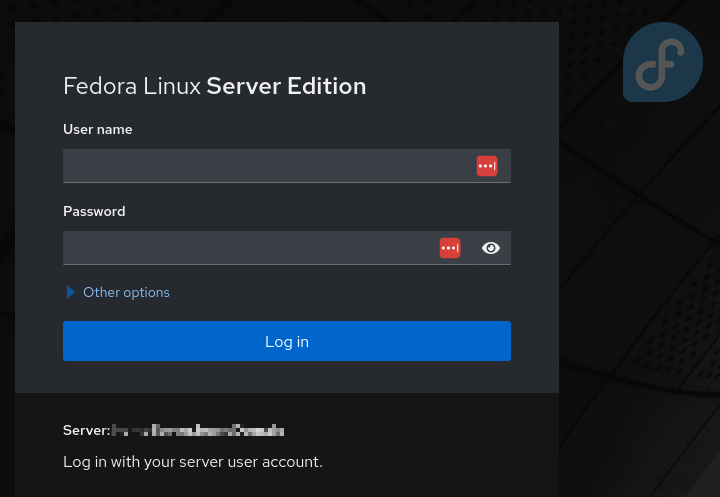

Cockpit is a graphical way to administer a Linux server – a service available by default in all RHEL family distributions (Fedora/CentOS/RHEL/Rocky/Alma) and many other distributions (see Cockpit Project for more details). The default (but configurable) port is 9090, so simply accessing <serverIP>:9090 in a browser results in a nice login screen.

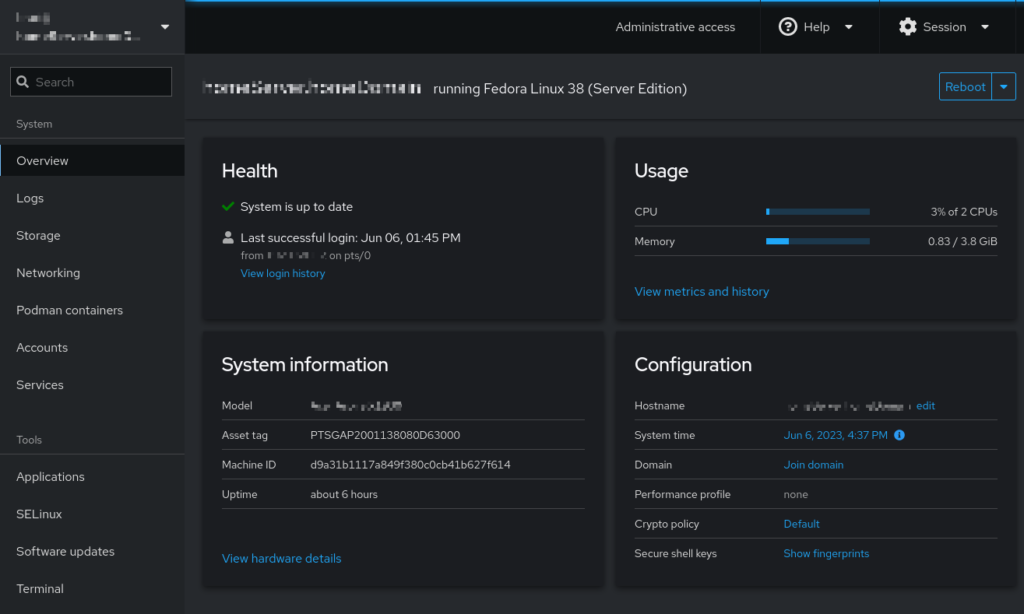

And then, naturally, Cockpit’s GUI presents many options:

Cockpit is robust – and can be used by everyone – beginning system administrators and experts alike. Viewing an individual server’s CPU/RAM, storage, network, and software services provides great observability. As you’ll see below, Cockpit is a systemd service; it runs on a socket only activated when someone is accessing it via the browser – thereby being very light on resources.

In a home lab, Cockpit is impressive—it does just about everything that a power user could ask for. It allows you to have remote control over a Linux server, hosting as many containers/services as you’d like, all visible from any device with a screen (yes, I use my phone to manage my home server because I can).

Installing Cockpit

Depending on your distribution, Cockpit may already be installed. If not:

sudo dnf install cockpit # RHEL Family

sudo apt install cockpit # Debian FamilyEnable the socket:

sudo systemctl enable --now cockpit.socketTo open the firewall ports (if needed), execute the following commands:

sudo firewall-cmd --add-service=cockpit --permanent

sudo firewall-cmd --reloadWhat is Podman?

Podman (Pod Manager) is an alternative to Docker within Linux, associated mainly with the RHEL family but also available in other distributions. Podman.io has tons of information (some very technical!). Still, in a nutshell, it has at least the same, if not better, functionality than Docker (the underlying mechanism is more Linux-kernel friendly). Even better, it is engineered to be command-compatible, so docker run -d -p 80:80 nginx and podman run -d -p 80:80 nginx yield the same results (all else being equal!).

While I find Docker and Podman largely interchangeable, Podman has the advantage of running rootless containers. This means that containers can run without root permissions and can even run based on a regular user ID even though that user is not logged in (once configured correctly). This means that servers, with all their extra horsepower and network connectivity, can host containers controlled by developers, not system administrators (or DevOps Enginerds like me). A developer can containerize their application and test its basic functionality and connectivity to the larger ecosystem, all without venturing into the complexity of a CI/CD toolchain until they’re sure the application works as expected. No more onboarding apps only to find that they don’t do half of the things that were in the requirements.

Managing Podman Containers in Cockpit

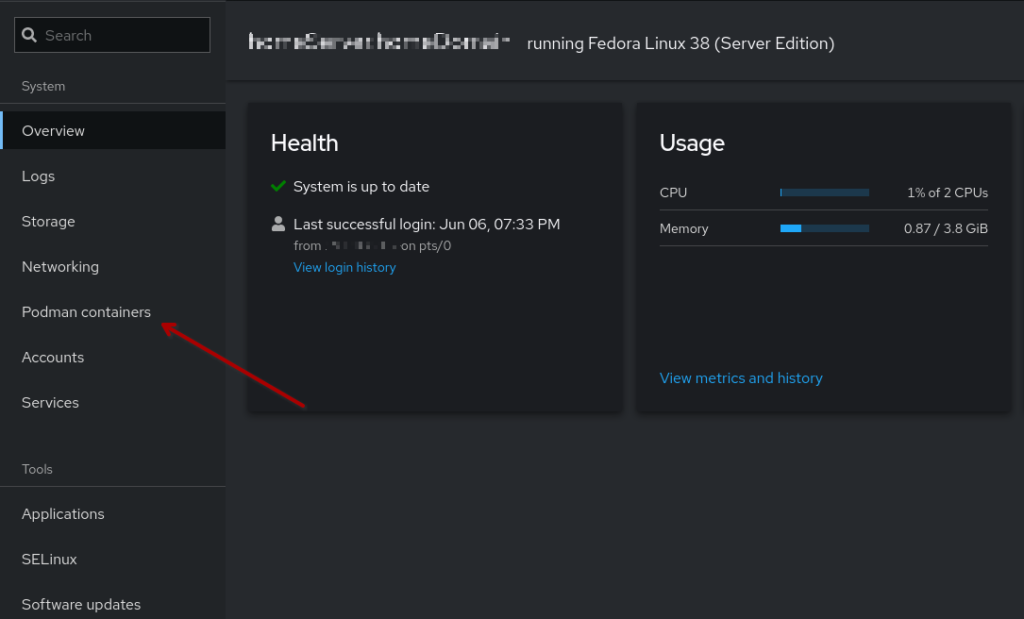

How do Cockpit and Podman work together? Amazingly – once you’ve installed the software. Assuming Cockpit is already up and running, run dnf install cockpit-podman (even while Cockpit is running) and suddenly, you’ll see a new menu item appear:

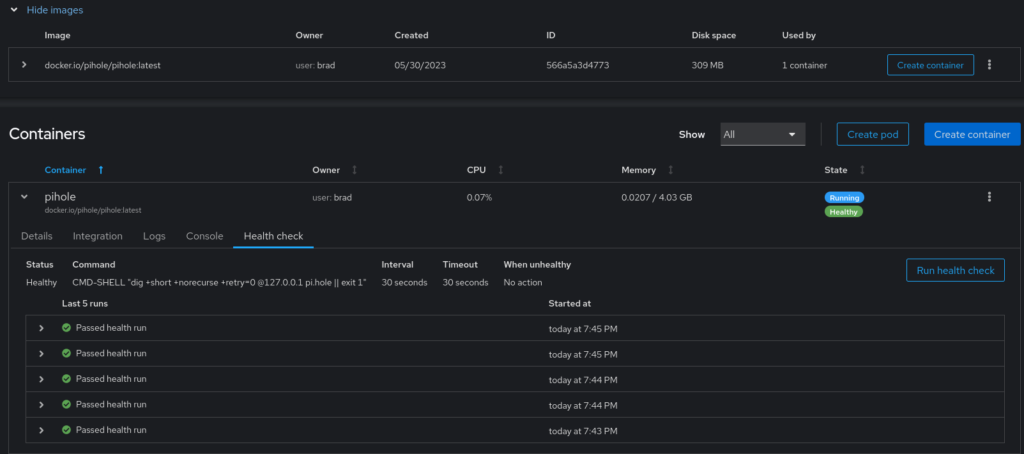

That menu gives you the ability to see a container as it is running and even shows you the health checks that the podman service is running on your container regularly:

As you can see above, I’ve spun up an instance of PiHole based on Running pi-hole as a podman container in Fedora to protect my home network from ads – that’s a story for another time!

So, with this power, a developer can use Cockpit to monitor the system resources their container is using, check its health, compare its performance to the server’s performance, and validate that their app works as expected and connects to all the other dependencies as it should. A world of possibilities opens up, all with a GUI to guide beginners and experts. It is even possible to create Podman containers in Cockpit, but realistically, this will most likely still be done via command line due to the anticipated complexity of most containers.

That’s Nice, But Why Would I Use This?

Onboarding to CI/CD pipelines is challenging. My style of work is to take one baby step at a time, ensuring what is behind me is solid and ready for the next step. I loathe situations where something is broken, and there are 496 items to check because we have changed 496 things since the last time we tried to run this. Change one thing at a time, and make sure that whatever was changed works before changing the next thing.

As mentioned above, this Cockpit/Podman duo helps to bridge the gap between “it runs on my machine” and “it’s in a Prod pipeline.” As much as we’d all like to be building purely cloud-native apps, the fact is that A LOT OF enterprise-grade computing is not yet cloud-native. There is still tons of local development happening, and the struggle between a git commit and a full-blown “app-in-a-CI/CD-pipeline” is often a drawn-out and painful exercise for everyone involved in creating software. The ability to test containerization on a real server and work with a GUI to see the health of the server and the container might make that pain go away or at least make it easier to manage.